By: Linda Fitzgibbon Ph.D.

On June 28, 1848, the Galway Poor Law Union Minute Book states: “a pauper named Jane Kelly had stolen from the garden of a person adjoining the temporary workhouse, 10 heads of cabbage. The Board directed that Jane Kelly be transmitted to the union workhouse and there to be kept in solitary confinement for 24 hours.”

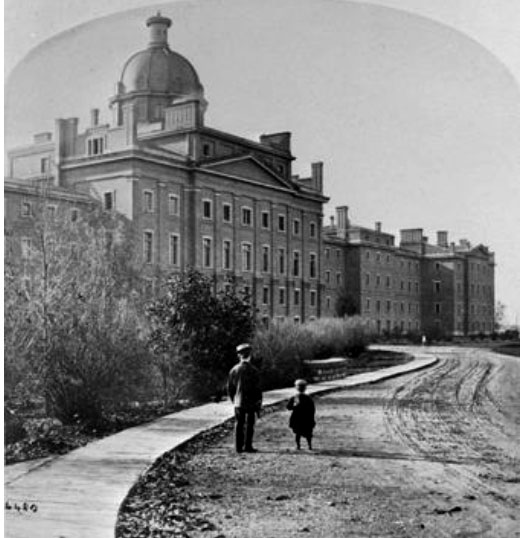

Jane Kelly’s unfortunate circumstances seemed to continue and by 1853 she had been a resident of Montbellew workhouse for five years and was part of a group chosen to emigrate to Canada. Aged 40, she was among the oldest of the group. Although listed as a tailoress, she does not appear to have found steady employment in Canada. In 1857, she was admitted to the Provincial Lunatic Asylum in Toronto. The 1861 Canadian census records her as a patient under the column “Lunatic or Idiot.” The records note that she is a widow. By 1871, the census reveals the changing view of mental health in Canada, as the Asylum has been renamed The Asylum for the Insane and Jane is listed as being of “Unsound Mind.” In 1881, Jane, now aged 69 years, is still an inpatient. Jane is listed as Church of England and her fellow patients, Church of England, Presbyterian, and Roman Catholic, are also Irish emigrants. Other inmates, male and female, include emigrants from England, Scotland, Norway and Germany and are from various religious backgrounds.

Jane is one of thousands of Irish women whose passages to the Colonies were paid for by the Poor Law Unions. Who were they? Where did the go? How did they fare when they got there?

Although they did not leave written records, institutional records such as: Records Books in The Asylum for the Insane in Toronto; Census Records; Reports submitted by the Emigration Officials in Canada to the Colonial Office in London; Records housed in Private Religious Archives in Canada, supplemented by information published in newspaper articles and advertisements, can provide clues on how these Irish emigrants fared in the New World and allow their stories to emerge. They were young, brave, and willing to risk crossing the ocean in the hope of finding a better life and a brighter future. Not all their stories are tragic. The records indicate that there are still many stories to be told and highlight the importance of continued research on female members of the Irish diaspora in Canada and continued exploration on how they helped to shape the emerging Canadian society.

Settlement of British North America was governed by a complicated structure. The Office of the Commissioner of Crown Lands was established in 1827. The 1841 Act of Union united Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada and the official emigration headquarters was established in Quebec (Lower Canada) with Mr. A. C. Buchanan in control. Mr. A. B. Hawke, who had headed the First Emigrant Office which had opened in Toronto in 1833 (Upper Canada), worked closely with Buchanan to recruit emigrants to settle the rapidly growing new country. The single Emigration Agency was controlled by the Colonial Office in London and until 1854, London supplemented the costs of recruiting emigrants.

The documents and reports filed by the Select Committee for the Poor Law reveal that Canadian and British officials were in close and regular contact with the Poor Law commission in Ireland. By 1850, the 130 workhouses, built in Ireland in 1836, had been extended to 163 and all were overflowing with inmates. The Canadian Emigration Office kept a detailed list of the numbers of emigrants who landed in the province, including those who had been sent out by the workhouses, and kept a close eye on their progress. For example, of the 32,648 emigrants who landed in Quebec in 1850, the Emigration Office noted where the emigrants settled and included information on the individuals who did not choose to settle in the province and who traveled on to the U.S. via Lake Champlain and via Ogdensberg.

On April 29, 1851, as was usual in the spring when navigation opened on the waterways in Canada, Hawke corresponded regularly with Buchanan as to how to deal with the expected incoming emigrants. On this occasion, they noted the necessity of finding “persons likely to require servants, as we are likely to have a very considerable number of single men and women who will be sent out by the Unions and charitable associations.” They also refer to “the 61 thousand young women!” who are available in the Unions and requested that the local authorities in Ireland should send “1,500 healthy decent young women, in parties of 500 each to Canada” and that they were confident that they would find places for that number in the province.

On September 22, 1851, Hawke wrote: “We got upward of 300 Union girls Thursday, the town [Toronto] being overstocked, I was obliged to send 30 to St. Catherines and nearly 100 to Hamilton. Both instances I wrote to the Roman Catholic priests to find them places.” This reference to contacting the Roman Catholic priests is important to bear in mind when attempting to locate some of the thousands of young women who were sent to Canada by the Poor Law Unions in Ireland. On October 13, 1851, Hawke wrote: “All the young women have been well disposed. I have had to call upon the priests at Toronto, St. Catherines, Hamilton and Cobourg. In writing to them, I claimed their assistance on two grounds. 1. That the girls were without natural protectors and secondly that they belonged to their church – they apparently took it very kindly.”

The large number of female emigrants continued to flow from the Irish workhouses through the emigration office in Canada and the Canadian officials paid for them to travel on to places in need of domestic servants. In 1852, Hawke refers to 230 newly arrived emigrants and is happy to report “the frequent applications arrived at this office for female servants.” The Canadian emigration officials paid the emigrants’ passages from Quebec to Toronto and directed that each girl should get an additional dollar because “some time must necessarily elapse before they get into work and it is to be borne in mind that they are not able to rough it, like journeymen.”

The Unions in Ireland were happy with this. The fare to Canada was cheaper than to Australia and was a practical way of removing the women from the workhouses. The committee in charge of emigration of inmates in the Cork Union reported: “Two years cost of maintenance of a female pauper would not only give her passage to the Canadian colony but would also leave a margin enabling her to have some money in her pocket on the termination of her voyage, so that she might not be utterly penniless on her arrival but would be in a fair way of earning a respectable livelihood.” [Irish Examiner, January 28, 1853]

At Poor Law Union Board of Governor meetings, there were many debates about finding ways to save money and the Union officials became adept at finding ways to ship out as many emigrants as possible while keeping costs at a minimum. For example, in April 1853: “The Urania, which sailed for Quebec, was chartered by the Poor Law Guardians of the Cork Union to convey young female paupers to the colony. She had on board 99, that number being selected, as the Passenger Act does not require that a Doctor should be on board unless there were at least 100.” [Neenagh Guardian, April 13, 1853]

The decision to send the paupers to Canada was justified by regular communications from Buchanan, Chief Emigration Agent with Government Emigration Agents in Ireland. A letter with reference to the “last batch” of females sent out from the Cork Union, read aloud to the Cork Union Board of Governors, quelled debate and ensured the continued approval of expenditure on chartering vessels to transport the inmates to Canada. Buchanan wrote: “I do not care how many robust young women you send us from Ireland, I have already made some enquiries and find there is no danger whatever of an over supply. I verily believe that more than one half of those who landed here last summer are already married, and of seven I sent to Thornhill, five had husbands and are doing well and reported to be in a thriving condition. You can inform the Guardians of the Cork union that on the arrival of the “Urania” party they shall have every care and attention.”

In fact, the officials in the Emigrant Office in Toronto were well satisfied with the supply of emigrants sent out from Ireland by the Poor Law Unions. At the end of the summer of 1853, Canadian officials were making plans to travel to Ireland to ensure that they could advertise Canada as a choice destination. As Hawke had written to Buchanan in July 1852: “I shall do all that I can because I feel that it is so important that all those who are induced to prefer Canada to the United States should feel satisfied that they have selected wisely and beneficially in so doing.” On August 21, 1853, they were even more enthusiastic: “the forty four Cork Union Girls . . . have all obtained places and if ten times the number landed here in the morning, they could be similarly disposed of.” The officials add: “Have any steps been adopted by the Government to induce emigrants to come to Canada in sufficient numbers to supply the existing and increasing demand? . . . Next year’s immigration might in my opinion be naturally increased if a discreet Agent – well acquainted with the Province was sent over this Autumn.”

The Emigration Agents had also found an efficient way of dealing with the Roman Catholic emigrants who did not find suitable employment. They remained in constant communication with the priests and, as they had taken pains to point out in September 1852, these emigrants “belonged to their church.” On June 8, 1853, the Emigrant Office in Toronto referred to the Athlone and Cork Union girls who have found places and noted that those who were not placed were sent on “with instruction to place them under the guidance of the Roman Catholic Priests.”

What is not noted in the Colonial Government, or the Irish Poor Law Commissioners’ reports is that when requested by the Emigrant Agents in Canada to provide assistance to the members of their flock who could not readily find places of employment, the priests turned to the female religious orders in Canada for assistance. The Sisters of Charity was established in Bytown [present day Ottawa] in 1845. Referred to as the Grey Nuns, these Sisters worked closely with the Roman Catholic priests. Through their schools, hospital, and their visits to the poor and sick in their homes, the Sisters contributed to the stability of this rapidly burgeoning area. The bi-lingual organizations they established became the backbone of social services in the city in the mid-to-late-nineteenth century. Therefore, it was no surprise that the priests turned to the Grey Nuns to help settle the newly arrived Irish girls who had been sent to them by the Emigration Agent. As early as 1848, the Grey Nuns in Bytown had taken in 70 “filles émigrés.”

By September 1852, the Emigration Agent, Mr. Burke was communicating directly with the Superior of the Grey Nuns Convent in Bytown and asked them to look after fifty young Irish female emigrants who had just arrived on the quay. On this occasion, six of the Grey Nuns went to collect the girls from the Bytown riverfront and noted that the girls seemed to be accustomed to religious ways, as they sang hymns and walked in pairs next to the Sisters. Because the emigrants were so tired, they gradually fell into single file and, as they passed, people in the houses came out to see them walk by. The Sisters collected

alms for the girls and in a short time had collected shawls, hats, and other clothing. As they settled into a house provided by the priests, Mr. Burke, the Emigration Agent, brought them bread, butter, and tea. By 1854, the Sisters were looking after 171 girls for whom the Emigration Agent paid “15 sols par jour” [per day]. In an 1854 Bytown Hospital report, Dr. J. Beaubien praised the Sisters for their work and noted that the Grey Nuns regularly looked after young female immigrants until they could be hired out in the city or in the adjoining country.

Some of these female emigrants were subsequently admitted as postulants. For these post-famine Irish emigrants, joining the convent provided an opportunity to work as part of an active and organized community. Although they did not attain important positions within the order, membership provided them with a safe place to work and a guarantee of security and support in their old age. Elisabeth Sergeant was admitted in 1856 and became a valued member of the community. Although she could not read or write, it is noted that she took pride in knowing the prayers by heart. She worked as a domestic in the boarding school and later in the Grey Nuns mission in Ogdensburg. She then was a door-keeper of the Notre Dame du Sacre Coeur until her death in 1901. When she died, Mother Dorothy Kirby, founding Superior of the Sisters of Charity mission in Ogdensburg, who had also been born in Ireland, spent the last night with her.

The different fates of Jane Kelly and Elisabeth Sergeant reflect just one slice of the history of thousands of Irish female emigrants who landed in Canada in the mid-nineteenth century. Unlike Jane whose last days in the Toronto Asylum are unrecorded other than on her death certificate, Elisabeth managed to secure a safe place and had a productive and satisfying career in a religious order. The rise in the number of vocations in the nineteenth century demonstrates that women were aware of the advantages of being part of a religious community. The vastly different experiences of these two Irish women provides a glimpse into the lives of the Irish diaspora in Canada and also highlights the complexity of Irish female immigrants’ experiences in Canada.

Notes:

Jane Kelly was born in Treanrevagh, County Galway in 1812. Civil Parish: Moylough. Poor Law Union: Mountbellew. Diocese: Tuam.

Jane Kelly’s name is on one of the passenger lists of Mountbellew paupers who were sent to Quebec. I subsequently found her name listed in the Canadian census 1861, 1871, and 1881. The Canadian census records are available online from the Library and Archives of Canada, Ottawa, Canada.

The information on Jane Kelly being “transmitted to the union workhouse and there to be kept in solitary confinement for 24 hours” as punishment for the crime of stealing “10 heads of cabbage” is found in the Minute Books from the Galway Poor Laws Union Records, Galway. 28 June 1848. Also available online.